What is atrial fibrillation?

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a type of abnormal heart rhythm where the heart beats irregularly – it may be rapid or slow. This is due to a problem in the heart’s chambers that collect the blood (atria). It is one of the most common heart conditions.

While AF itself may not be dangerous, it is important to diagnose and treat it because it increases the risk of other conditions, such as heart failure and stroke. Even if the AF does not present with any symptoms, it is still important to treat it.

In AF, blood circulates in the heart in an abnormal way, so there is a tendency for blood clots to develop (thrombosis). These clots can break off and travel to all areas of the body in the bloodstream. If a clot blocks a brain artery, this can cause a stroke.

Recent research by the Heart Research Institute (HRI) has also confirmed a strong link between AF and dementia.

A clear pattern has been found between the incidence of AF and First Nations peoples. HRI’s study saw that Native Americans, Aboriginal Australians and Māori and Pacific people in New Zealand experience higher levels of AF at an earlier age.

Symptoms of atrial fibrillation

AF may not cause any symptoms, or the symptoms may only occur some of the time. AF can remain undetected for long periods of time, which is why it is so important to screen for AF.

Common symptoms of AF include:

- heart palpitations

- racing or ‘fluttering’ heartbeat

- irregular heartbeat, which can be detected by checking the pulse

- pain or discomfort in the chest (angina)

- breathlessness, especially during activity

- dizziness and light-headedness

- tiredness and weakness.

Types of atrial fibrillation

There are several types of AF.

- Occasional AF (paroxysmal AF): AF can start and stop suddenly, lasting for minutes to hours and even up to a week. Episodes can come and go, and may stop on their own without treatment or happen repeatedly. Some episodes have symptoms which can be very concerning, while other episodes have no symptoms at all.

- Persistent AF: AF episodes can last longer than a week, and the heartbeat does not return to a normal rhythm on its own. Treatment with “electrical shocks” or medication is needed to restore the heart rhythm to normal.

- Permanent AF: AF is continuous and long term, and the heartbeat cannot be restored to a regular rhythm. Again, symptoms may not be present. Medication is needed to help control the symptoms and to prevent blood clots.

AF is progressive and gets worse over time. This means occasional AF could develop into persistent or permanent AF.

What causes atrial fibrillation?

The cause of AF is not always clear, but it originates in the heart.

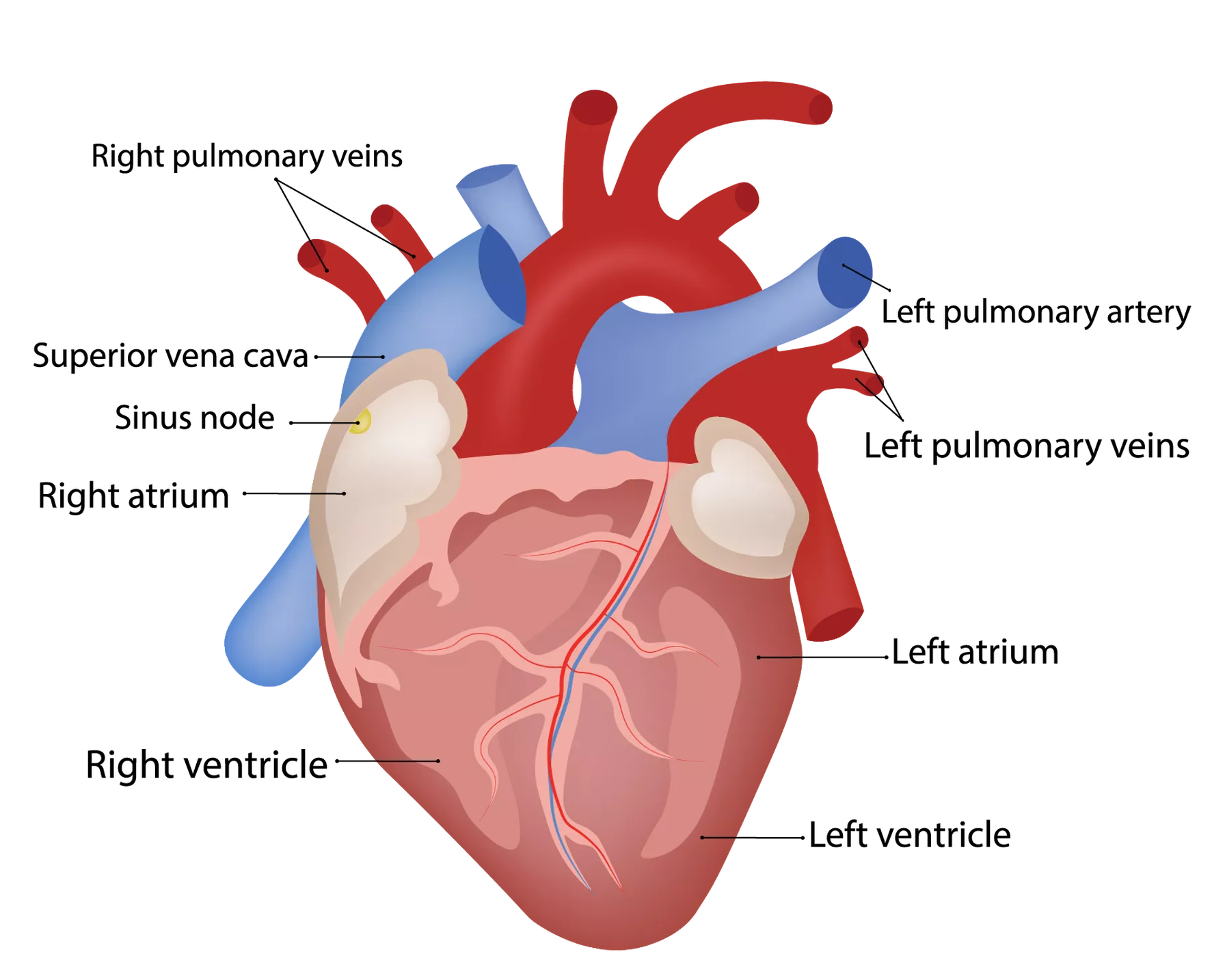

The heart is comprised of four chambers: two upper chambers (the atria) and two lower chambers (the ventricles). The right atrium contains the heart’s natural pacemaker, called the sinus node, which produces the electrical signal that starts each heartbeat.

Anatomy of the heart

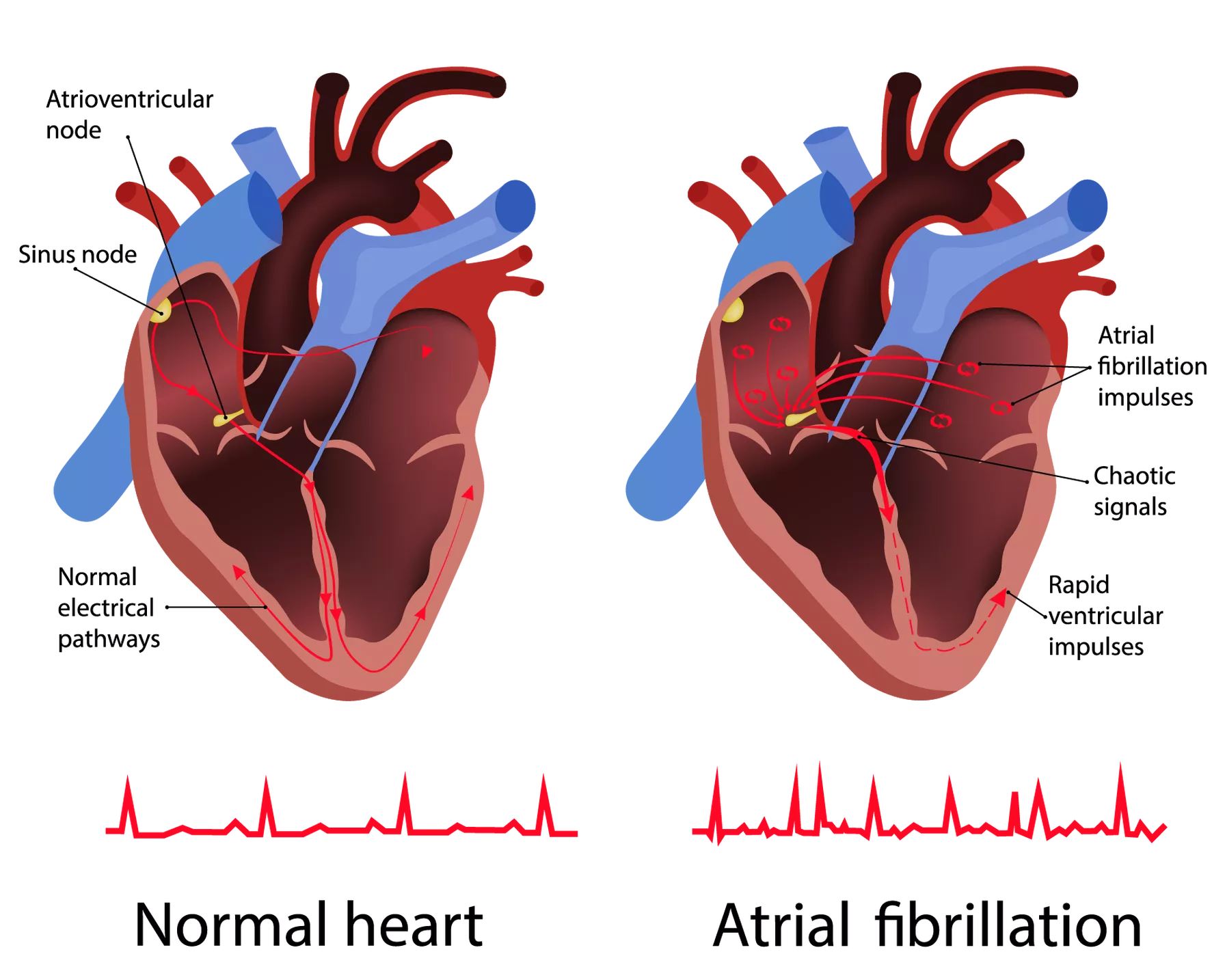

In a regular heart rhythm, the signal passes through the upper chambers of the heart to the lower chambers, causing the chambers to contract and relax in a steady rhythm. This regular heartbeat allows the heart to effectively pump blood to the rest of the body, supplying the organs with essential oxygen and nutrients.

In atrial fibrillation, the upper chambers of the heart twitch erratically instead of contracting. As a result, the electrical messages sent to the lower chambers of the heart cause them to contract irregularly and sometimes very rapidly. This affects the heart’s ability to pump efficiently. The abnormal circulation of blood in the heart increases the risk of blood clots forming, which could break off and travel to block a brain artery, causing a stroke.

The normal resting heart rhythm is regular, with a rate usually between 60 to 100 beats per minute. In AF, the rate may be faster and is often over 100 beats per minute and up to 175 beats per minute.

In atrial fibrillation, distorted electrical messages sent to the lower chambers of the heart cause them to contract rapidly and irregularly.

Atrial fibrillation impact in the UK

AF is very common, affecting over 1.6 million people in the UK. Around an estimated 300,000 people are unaware that they are living with AF.1

The risk of developing atrial fibrillation

AF can occur in both men and women, and can occur at any age, though it is more common in those over 75 years of age. The most common causes of AF are ageing, having long-term high blood pressure, diabetes or coronary heart disease, although the cause is not always known.

Over the age of 40, you have a one in three lifetime risk of developing AF.

As you get older, your risk of developing AF increases. About seven per cent of people over 65 have AF, and this increases to 10 per cent over the age of 75.2 At this stage, screening for the condition becomes even more important due to the increased risk of an associated stroke.

The risk of AF is also increased by the following factors.

- Heart disease: Anyone with heart disease or a history of heart attack or heart surgery has an increased risk of AF. Heart defects from birth (congenital heart disease) can also increase the risk.

- High blood pressure: This can increase the risk of AF, particularly if not controlled by lifestyle changes or medication.

- Other chronic health conditions: Sleep apnoea and diabetes can increase AF risk, as can other chronic conditions such as kidney disease and lung disease.

- Stimulant use: Smoking, alcohol, caffeine and certain medications may trigger episodes of AF, and long-term alcohol use can lead to persistent AF.

How to decrease your risk of atrial fibrillation

There is a strong association between AF and high blood pressure, a sedentary lifestyle and obesity. Simple lifestyle changes such as the below could help to prevent and manage AF as well as improve overall health and wellbeing.

- Control high blood pressure through medication or dietary changes

- Exercise regularly, such as by setting up your own exercise program

- Reduce alcohol consumption

- Manage diabetes through diet or medication

- Quit smoking

Risks associated with atrial fibrillation

The main danger of AF is the associated risk of stroke. This is present even if AF is only experienced some of the time, and whether or not the AF shows symptoms. One in every three strokes is linked to AF, and AF-linked strokes are more severe than other strokes. People with AF are also five times more likely to have a stroke compared to those who do not have AF.3

The risk of an AF-associated stroke occurring is also higher if you are older than 65, and if you have high blood pressure or diabetes, or have had a previous stroke, or if you have heart failure.

Other heart problems, such as heart attack and particularly heart failure, are also more likely to occur in people with AF.

People with AF are also at increased risk of dementia. This link is independent of stroke and other risk factors, although whether the link is causal is not yet known.

Screening for atrial fibrillation

To screen for AF, your doctor may take your medical history and do some tests, such as:

- a physical exam and checking your pulse

- blood tests to rule out other causes

- taking an electrocardiogram (ECG), the main tool for diagnosing AF which measures the heart’s electrical activity

- taking an echocardiogram, an ultrasound that produces moving pictures of the heart that can help show structural heart disease or blood clots in the heart.

As AF symptoms are intermittent, the use of a portable ECG device may be needed. Handheld ECGs and smartwatches with ECGs are increasingly available to consumers.

Medical devices can be worn by patients to record the electrical activity of their heart for longer periods of time, increasing the chance that the AF symptoms will be recorded. A Holter monitor can be used to record the heart’s activity for 24 hours or longer, while patches can record for two weeks. An event recorder can be used to record the heart’s activity over weeks to months.

Self-screening for atrial fibrillation

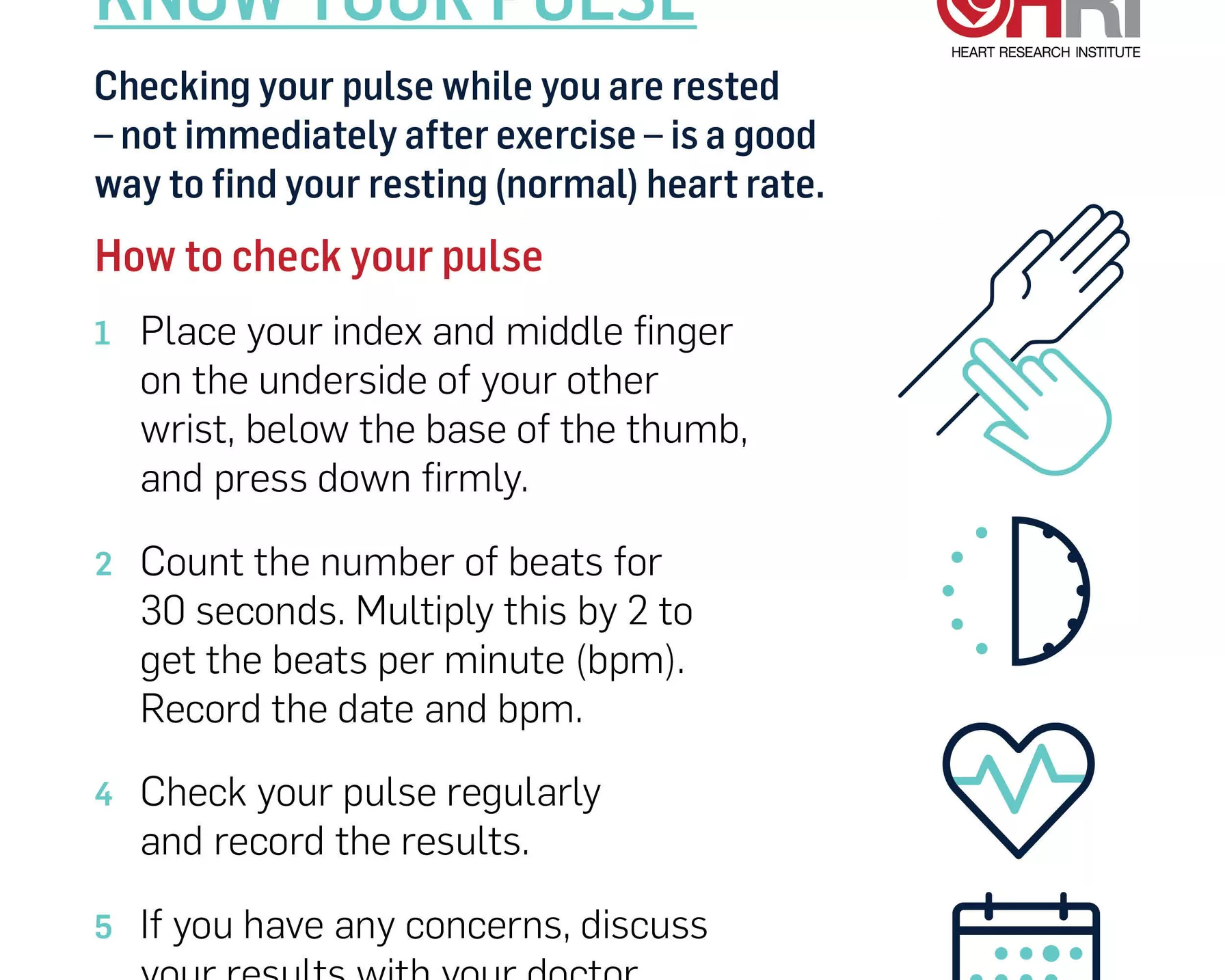

While only your doctor can diagnose AF, you can keep an eye on your heart health by regularly checking your pulse. Your pulse can indicate how well your heart is working, how fast it beats, and its rhythm and strength. Keeping a record will help you notice if there is anything different or unusual with your results.

A normal pulse, or resting heart rate, ranges from 60 to 100 beats per minute. Your pulse should beat steadily and regularly. A pause or extra beat now and then is normal, but if you notice frequent skipped or extra beats, speak to your doctor. Also speak to your doctor if your pulse is consistently outside the normal range, as this may indicate an underlying problem.

To check your pulse:

- Place your index and middle finger on the underside of your other wrist, below the base of the thumb, and press down firmly.

- Count the number of beats for 30 seconds. Multiply this by 2 to get the beats per minute (bpm). Record the date and bpm.

- Check your pulse regularly and record the results.

- If you have any concerns, discuss your results with your doctor.

Checking your pulse regularly can help you stay on top of your heart health and your risk of atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation treatment

Once AF is diagnosed, medication can be prescribed with the following purposes.

- Normalise the heart’s rhythm: These anti-arrhythmic medications can be given as injections or tablets.

- Slow the heart rate: These include beta-blockers and some calcium channel blockers.

- Reduce the risk of stroke: Anticoagulant medication (blood thinners) significantly reduce the risk of stroke in people with AF.

Electric shock therapy to the heart (electrical cardioversion) is another treatment for AF. Given under general anaesthesia, this electrical shock to the chest helps to “reset” the heart’s electrical system. Long-term medication may be required post-therapy to maintain the heart’s normal rhythm.

While most cases of AF respond to these treatments, in severe cases surgical options may be required. One option is implanting a pacemaker in the heart to electrically stimulate it to maintain a regular rhythm.

Living with atrial fibrillation

The irregular occurrence of AF episodes can be stressful, but there are a number of steps you can take to help you stay on top of your AF and continue to live a full and active life.

- Follow your doctor’s advice carefully. Your doctor may advise lifestyle and dietary adjustments, and provide strict guidelines around any prescribed medications. Follow these carefully for the best health outcomes.

- Keep a record of your symptoms. Write down whenever you experience an AF episode and how long it lasts, as well as any other symptoms. Bring this record to your next doctor’s appointment.

- Check your pulse regularly and keep a record. Take your own pulse regularly, and keep a record to show your doctor. This will help highlight if there are any changes in your heartbeat to keep an eye on.

- Learn your triggers. In some people, bouts of AF can be triggered by certain foods, exercises, stimulants or even stress. Noting down the context each time you experience AF can help you to identify whether you have a trigger and to avoid it in the future.

How is HRI fighting atrial fibrillation?

HRI is tackling the widespread problem of AF from a broad range of research angles. The mission of our Heart Rhythm and Stroke Prevention Group is to prevent as many strokes as possible through early detection of silent AF, and to implement appropriate guideline-based management. With a clinical implementation focus, the Group is exploring novel strategies using eHealth tools and patient self-screening to detect unknown silent AF.

If screening for AF could be implemented more widely in people aged 65 and older, along with preventative treatments being prescribed as advised in guidelines, then thousands of strokes could be avoided globally, making a difference to patients and their families.

References

- British Heart Foundation UK.

- Atrial Fibrillation Association Australia. Atrial Fibrillation (AF) Patient Information. 2013.

- Wolf PA et al; Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1991;22:983–988.